I was told they were currently featuring an exhibit from Ai Weiwei at the Art Gallery of Ontario. You’ve probably heard of Ai Weiwei even if you don’t think you have. He’s the Chinese dissident artist who was put under house arrest back in 2010 for his opposition to the communist government. The exhibit showcased a range of Ai Weiwei’s works, and I found it to be one of the most intereting and enjoyable art experiences I’ve ever had. Weiwei’s style is smart, but not esoteric. His pieces make you think but they don’t aim to confuse. And he has a sort of puppet master appeal, because he often doesn’t make the pieces himself. Rather, he explains his vision and ideas to other artists, who then create it and expand upon it. Some pieces were simple, like the 12 foot long log with an outline of China carved straight through the middle. Or the beautifully crafted wooden walls lined up line dominos, so that when you look through the holes in the center you see the phases of the moon. Or, I suppose, that’s what you’re supposed to see. More often than not you looked through and saw another patron staring back at you, usually holding a camera.

I was told they were currently featuring an exhibit from Ai Weiwei at the Art Gallery of Ontario. You’ve probably heard of Ai Weiwei even if you don’t think you have. He’s the Chinese dissident artist who was put under house arrest back in 2010 for his opposition to the communist government. The exhibit showcased a range of Ai Weiwei’s works, and I found it to be one of the most intereting and enjoyable art experiences I’ve ever had. Weiwei’s style is smart, but not esoteric. His pieces make you think but they don’t aim to confuse. And he has a sort of puppet master appeal, because he often doesn’t make the pieces himself. Rather, he explains his vision and ideas to other artists, who then create it and expand upon it. Some pieces were simple, like the 12 foot long log with an outline of China carved straight through the middle. Or the beautifully crafted wooden walls lined up line dominos, so that when you look through the holes in the center you see the phases of the moon. Or, I suppose, that’s what you’re supposed to see. More often than not you looked through and saw another patron staring back at you, usually holding a camera.

One of my favorite pieces was a pile of plastic crabs. In 2010, the Chinese government ordered that Weiwei’s new studio had to be destroyed because of supposed planning permission infractions. Weiwei organized a party to celebrate the demolition, but was kept from attending the celebration himself. The party happened without him and the guests feasted on River Crabs. The plastic pile at the museum was an homage to the party, and the crabs themselves were a dig at the government. The term “River Crab” has become synonymous with Chinese censorship in many internet communities, because the Chinese word for River Crab sounds very similar to the Chinese word for Harmonious – as in the government’s drive towards a supposedly “Harmonious Socialist Society.”

One of my favorite pieces was a pile of plastic crabs. In 2010, the Chinese government ordered that Weiwei’s new studio had to be destroyed because of supposed planning permission infractions. Weiwei organized a party to celebrate the demolition, but was kept from attending the celebration himself. The party happened without him and the guests feasted on River Crabs. The plastic pile at the museum was an homage to the party, and the crabs themselves were a dig at the government. The term “River Crab” has become synonymous with Chinese censorship in many internet communities, because the Chinese word for River Crab sounds very similar to the Chinese word for Harmonious – as in the government’s drive towards a supposedly “Harmonious Socialist Society.”

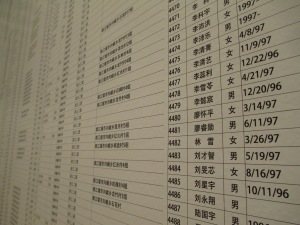

The piece that really stuck in my mind was the wall of names. In 2008 a powerful earthquake hit the Sichuan province. Do you remember it? I didn’t. I asked my friends and family. Sometimes they said it sounded vaguely familiar, though they were’t sure that they weren’t confusing it with some other disaster. “Was it a big earthquake?” they would ask.

It killed 70,000 people.

When I heard that figure quoted in the gallery documentary I couldn’t believe it. How did 70,000 people die in an earthquake and I can’t remember anything about it? The 2011 Japanese Tsunami only claimed around 18,000 lives, yet it’s burned into many of our minds.

When I heard that figure quoted in the gallery documentary I couldn’t believe it. How did 70,000 people die in an earthquake and I can’t remember anything about it? The 2011 Japanese Tsunami only claimed around 18,000 lives, yet it’s burned into many of our minds.

One reason for this is that accurate death toll numbers were not easy to come by. According to Weiwei and other dissidents, the government obscured the numbers and kept many from learning the truth: over 5,000 of those deaths were children killed when their government-built schools collapsed. Weiwei participated in a citizen’s investigation, uncovering the names of 5,385 children. These names were listed alongside their birth dates and other information on the wall of the exhibit. The list consumed the entire gallery wall. Five thousand souls lost and nearly forgotten, all in an attempt to hide the sad and embarrassing truth the children had been living in.

If Ai Weiwei’s goal was to make me understand the power of a government in absolute control, he did it. We like to think that the limits of government control extend to all the taxes we don’t want to pay. We like to think that no great evil can hide forever, and that the truth will out eventually. We like to think that economic equals are societal equals. But it’s not always the case. When a government can lock up its artists, its dissidents, it can do anything. It can declare safe things dangerous. It can declare dangerous things safe. The earth can move, and they can make it disappear.

If Ai Weiwei’s goal was to make me understand the power of a government in absolute control, he did it. We like to think that the limits of government control extend to all the taxes we don’t want to pay. We like to think that no great evil can hide forever, and that the truth will out eventually. We like to think that economic equals are societal equals. But it’s not always the case. When a government can lock up its artists, its dissidents, it can do anything. It can declare safe things dangerous. It can declare dangerous things safe. The earth can move, and they can make it disappear.